Valentine’s Day may bring to mind hot-pink hearts, purple chocolate boxes, and red rose bouquets… but why not tinge it with a bit of blue?

Today is also the anniversary of the “Pale Blue Dot” image—a portrait of Earth from 3 billion miles away. Read more below about the romance of space and pictures of faraway planets!

On February 14th, 1990, the spacecraft Voyager 1 snapped an image of Earth from over 3 billion miles away. Carl Sagan dubbed this view of our planet “The Pale Blue Dot,” and his speech says more about our place in the universe than I could ever hope to convey.

But I’m going to try anyway—by taking you on a little journey through planetary portraits.

The Pale Blue Dot was the first image of Earth we’d ever taken from the outer solar system, and the last series of images Voyager 1 ever took. Space scientists Candy Hansen and Carolyn Porco developed the commands and calculated the exposure time, making for awe-inspiring views on February 14th… which were then saved to an on-board tape recorder and sent back to Earth from March through April. When they were finally sent, the signals rushed back at the speed of light, but still took 5.5 hours to reach home. Earth appeared smaller than a single pixel, awash in camera-bent sunlight, surrounded by nothing but empty space and optic noise.

2020 remastered version of the “Pale Blue Dot” image, taken by Voyager 1

In the 33 years since the Pale Blue Dot image was taken, we’ve traveled back to the outer solar system and snapped another photo: the Cassini spacecraft’s image of backlit Saturn, where Earth hangs out beneath clean-cut rings. Our planet seems a bit less lonely in the shadow of a gas giant.

The Day the Earth Smiled (2013)

But Earth isn’t the only planet we’ve seen from afar. In 2004, we took our first-ever image of an exoplanet, or a planet that orbits another star beyond our solar system. These are whole other worlds, with each their own history.

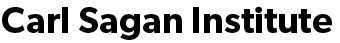

Some exoplanets orbit one star like us, while some orbit two stars, maybe even three; some exoplanets are rocky, while some are made of gas. Some exoplanets are as large as Jupiter and whiz around their star in under a week. There is an exoplanet that takes one million years to orbit its star. There is a red-hot dot where gems might fall from clouds of metal, and there is a deep blue dot where glass might rain sideways. But in all our searching, we have not yet discovered a planet like Earth—a planet with life.

Since 2004, we’ve taken pictures of a few more exoplanets, including the one that takes a million years to orbit its star (COCONUTS-2b). Even the James Webb Space Telescope has gotten in on the action. But these images reveal no more about their planets than the Pale Blue Dot might reveal to an alien.

Top images from left to right: Beta Pictoris b, four planets of HR 8799, 51 Eridani b

Bottom: 2M1207b (the first exoplanet ever imaged), HD 106906b, PDS 70

Most of the time, we don’t even have any pixels, or any image of the exoplanet we’re studying. Direct imaging is just one way to find an exoplanet—and it falls far from being the most prolific method. As of February 2023, only 48 of over 5000 confirmed exoplanets were found through direct imaging, compared to thousands found through the “transit method.” The transit method measures the dip in starlight as an exoplanet passes in front of its star. This method only needs to measure the total amount of light coming from a certain place. It’s much harder to pinpoint where that light is coming from, and to collect that light in separate boxes, or pixels, in the direct image.

Voyager 1’s camera was able to pick out Earth from 3 billion miles away. Imagine we were aliens taking a picture from quadrillions of miles instead, where our tiny dot would seem to run a tight lap around the sun, dimmer than candle flame beneath a flood light. With our current technology, we’ve been unable to detect any Earth-sized exoplanets that orbit as far from their star as we do—and much less take a picture of them.

What’s so special about the 48 we did snap a photo of? Those happy few exoplanets could only be imaged because they’re very young, making them bright as far as planets go. Newly formed planets glow red hot, as Earth did before its crust cooled down. After cooling, the light of the star tends to drown out its planets far too much for them to be imaged.

Because these directly imaged planets are young and hot, they’re unlikely to host life. A magma-mired planet isn’t likely to hold delicate organisms—and there hasn’t been enough time for them to evolve yet.

Carl Sagan’s words still ring true. There is no evidence yet for life beyond Earth, not on directly imaged planets and not on any of the 5000 discovered. But we’ve found tens of planets in the “habitable zone,” ones that might host liquid water on the surface. And what about all those planets we can’t detect yet—ones that are too dim, or too small?

Maybe there’s life out there, lying just beyond our reach for now—dots like ours, in pale blue or green, in purple or pink or red. But for now, Earthlings are the only beings we know. We’re cocooned in our atmosphere, our eight planets, countless asteroids, and the solar system’s Oort Cloud. We’re light years away from any exoplanets. It’s easy for the empty space to weigh upon us.

So it’s a good thing none of us face that space alone.

I tried my best to convey our place in the universe, but in the end, Carl Sagan’s words are still the best way to sum up your Pale Blue Valentine’s Day. From the dedication in Cosmos: “In the vastness of space and the immensity of time, it is my joy to share a planet and an epoch with Annie.”

If Pale Blue Dot Day is about recognizing our place in a tremendous universe, loving the world—and worlds—we discover, then it fits right in with a romantic holiday. But it’s not just for “every young couple in love.” Once the red roses, red chocolates, are bought and given, February 14th is a day to celebrate everyone we’ve ever known, everyone we’ve ever loved. Today we should tinge our reds with a little pale blue, too.